Following the Money: How and What We Reimburse Doctors for Matters

There is growing recognition that a re-orientation of our nation’s health care system towards prevention and quality is underway. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) seeks to forge a path to a new era of health care reimbursement based on the “triple aim”: 1) improving the patient experience, 2) facilitating better health outcomes, and 3) reducing the per capita cost of health care. It turns out that it matters how and what we pay for to improve the delivery of care.

What is the fee for service reimbursement model? What’s wrong with it?

The fee for service (FFS) reimbursement model is the way most health care services are financed and is the system most familiar to Americans when visiting their provider. In short, it is a way of billing the payer for each health care service delivered (like an office visit, test, or procedure). The health system or health care provider sends you or your insurance company an invoice with the services that were delivered.

Why is this a problem? Economists worry it incentivizes physicians to bill for more treatments, labs, or visits because the payment they receive is dependent on the quantity of health care services they deliver. By doing this, it creates a potential conflict of interest with patients since health care systems are rewarded for performing duplicate tests, over-prescribing medications, providing more health care services than is required, and other strategies to maximize the amount of billable care.

One of the most concerning and perverse problems with the FFS reimbursement model is that it is not aligned with efforts to prevent disease and promote health. As health deteriorates, it results in more opportunities for billable health care services (e.g. more lab tests, visits to the doctor or emergency room, and prescriptions). Since efforts to engage patients in prevention and health promotion have low reimbursement rates, or are not reimbursed at all, health systems are effectively penalized financially for developing innovative care models that keep people from getting sick. In other words, it makes more financial sense from the health system’s perspective to bill for an expensive surgery than it does to have a health coach or nurse work with patients to make lifestyle changes to prevent or alter the trajectory of their disease, perhaps eliminating the need for expensive and invasive surgery.

Where has this approach led us?

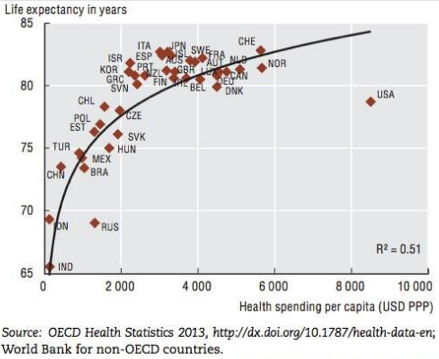

In the US we pay far more than any other country in the world for health care, but all of that money doesn’t translate into the best health. Despite our highest per capita spending on health care, we have a lower life expectancy compared to other developed nations. It demonstrates the need for a system that encourages greater efficiency and a focus on prevention.

What’s the alternative?

It will take a nuanced approach to balance the competing goals of reducing costs and improving the health of patients. Whatever the funding mechanism, there’s a moral and financial imperative to create a system that incentivizes a more rational approach to reimbursing for health care services.

An often-underappreciated aim of the ACA is the focus on moving away from FFS towards a model of health care financing that takes into account quality and efficiency. Included in the ACA, the Accountable Care Organization (ACO) is a new type of healthcare organization that aims to improve quality and reduce the total cost of care for a population of patients. This can be achieved via different types of payment plans. The alternative being tested by emerging ACOs and larger health systems is known as a value based reimbursement model. The goal is to incentivize and reimburse based on what everyone agrees is the ultimate measure of a successful health care experience, better health. Collecting data to understand which health care services improve health outcomes and penalizing health systems that bill for unnecessary testing or are constantly readmitting patients due to complications are critical first steps.

The health care delivery model of the future will be one that embraces the ethos of personalized, patient centered and proactive care. It will be designed to predict disease, personalize prevention and treatment, and collaborate with patients to help them reach the highest levels of wellness. Providers and health care systems are capable of developing these types of innovative delivery models, so long as we accelerate movements towards reimbursement reforms that support and incentivize this more rational and compassionate approach to medicine. By incentivizing quality over quantity, we’re moving in the right direction.